There’s something uniquely special about secondhand books, a book with a history of its own, whether its a well-worn, heavily annotated copy of a classic or an out-of-print obscurity. In the case of the latter, it can feel like no one else in the world has read the book but you, that the writer might as well have been writing a letter specifically for you. So it feels oddly fitting that the novel Over the Hills and Far Away,1 a novel all about loneliness and all about the relationship between people and books, would end up being a book so seldom read.

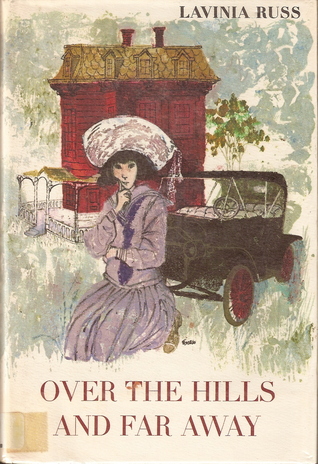

I acquired the book as a child, picked up free from the Traveler Restaurant, a roadside restaurant in Connecticut where diners get a free secondhand book of their choosing with every meal. Information about the author or the book is scant. It was published in 1968 as part of Harcourt’s2 Weekly Reader Children’s Book Club. The author, Lavinia Russ, like the protagonist of Over the Hills, was born in Missouri. Starting her writing career at the age of 57, she published seven other books in her lifetime, including a sequel called The April Age.3 Nominated for a minor children’s book award,4 today Over the Hills has only four reviews on Goodreads.

Either way, I have the impression that I would have gotten along with Russ. She spent much of her life working in the Scribner’s Bookstore in New York, and wrote loving about books–and, indeed, about people. In Richard Goodman’s A New York Memoir, he meets an elderly woman named Lavinia Russ that I can only assume is the same Lavinia. She is described as lively and strong-willed, with “formidable” eyes that had something “dramatic and essential” to them.5

As for the novel itself, Over the Hills and Far Away (also published as And Peakie Lived Happily Ever After) is about a young girl growing up in Missouri in 1917. Presumably at least somewhat autobiographical, the novel is superficially similar to other vintage children’s books for girls such as the Betsy-Tacy series or even the Laura Ingalls Wilder books. It focuses more on short anecdotes, such as Peakie’s father reading Peter Pan to her while they’re sheltering from a storm, or her correspondence with an I.W.W. organizer, than overarching plot.

But all this is written in a voice so singular and authentic it puts Holden Caulfield to shame. Writing child characters is a difficult task for any writer, but Russ accomplishes it with grace from the opening lines: “Nobody ever tells you how they felt when they were growing up. Not how they really felt. Maybe they can’t remember. But I know how I feel…I’m almost twelve, and I have a square face.”7 Russ, refreshingly, refuses to romanticize Peakie or, alternatively, to mock her. Peakie, with all the mistakes she makes in the book, whether from simple ignorance or from misjudgement, is given dignity within the narrative. It is clearly understood that she is still a child, and she is written as such.

A deep love of poetry and literature permeates the entirety of Over the Hills. Peakie feels embarrassed for crying while memorizing poetry and has an imaginary friend in Jo from Little Women. References and quotes from novels or poems are interwoven throughout the text, which makes sense, given what little information I’ve managed to find about Russ’s life.

There was something about Lavinia Russ that I haven’t yet mentioned. She was not only an author but a book reviewer for Publisher’s Weekly and the New York Times. Passionate about children’s books, she kept her finger on the pulse of the literary world.

But out of all the books she encouraged children to read (“If they don’t choose their own books after [the age of ten], they’re in trouble — and so are you”),9 there was none she was more passionate about than Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women, much like her protagonist Peakie. In fact, later in the same year as the publication of Over the Hills and Far Away, she wrote an essay which neatly explains what drew her to write her first children’s book at the age of 57, and why she chose Jo March to play such a central role in it: “Nineteen sixty-eight seems a strange time to talk about Little Women, and I seem a strange choice to do the talking. Of course there is an obvious reason for the date…a neat one hundred years since Little Women was first published.”10

In 1968, Lavinia Russ published a children’s novel in commemoration of the one hundred year anniversary of her favorite novel, and though it might have entered the world without so much as a ripple, it remains to this day my favorite childhood book.

NOTES

1 Lavinia Russ. Over the Hills and Far Away. (New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, Inc., 1968).

2 That is, when Harcourt was still called Harcourt, Brace & World, Inc.

3 For more information on her life, see her obituary in the New York Times archives.

4 Dorothy Canfield Fisher Children’s Book Award (nominated 1970).

5 Richard Goodman. A New York Memoir. (New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 2011), 25.

6 Desmond Stone. Alec Wilder in Spite of Himself: A Life of the Composer. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996). Photograph courtesy of Michael Geigher.

7 Russ, 9.

8 Russ, personal comment.

9 Lavinia Russ. The Girl on the Floor Will Help You. (New York: Doubleday, 1969).

10 Lavinia Russ. “Not to Be Read on Sunday.” The Horn Book, Vol. XLIV, No. 5. (1968), 521.

What a lovely review, Ginevra! Because of your review, I have ordered the book, both to read myself and to share with my grandchildren. I look forward to reading it. Thank you!

LikeLike

Thank you so much! I hope you & your grandchildren enjoy the book!

LikeLike