Mary Shelley, writing her masterpiece in pre-Victorian England, was living at a time when the majority of biological science was still a complete mystery. Frankenstein was published five years before the invention of the stethoscope, and modern medicine was still in its embryonic stages, with its possibilities seeming almost limitless. Anaesthesia began to blur the line between life and death, allowing physicians to perform more dramatic operations than ever before, and Jean-Baptiste Lamarck was developing a pre-Darwinian theory of evolution, what he called transmutation. While soon superseded by Darwin’s theory of natural selection, what would most surprise a modern reader of Lamarck would not be his theory of inheritance, but something else entirely–his conception of creation.1

Lamarck believed in spontaneous generation, the idea that life regularly arose from non-life, such as maggots arising from rotting meat. This was not a fringe theory but accepted scientific fact. The beginning of life, in other words, was still very much shrouded in mystery. When Mary Shelley published Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus in 1811, neither the male or female mammalian gametes had been identified, and it would be almost half a century before Cell Theory would conclusively disprove spontaneous generation.

In a pre-Darwinian world, even the most analytically-minded scientist could not think of the beginning of life as anything short of miraculous. Bringing the dead back to life, then, could not have seemed that far of a stretch.

Derek Attridge describes creation as arising from conflict, specifically internal conflict between a person and their culture. The exact mixture of cultural “habits, cognitive models, representations, beliefs, expectations, prejudices, and preferences” that shape an individual’s experience of the world is what Attridge calls an idioculture.2 An idioculture is “divided and contradictory…its semblance of coherence sustained by the repression or exclusion of some elements and possibilities, subject to constant challenge from the outside as well as to outgoing tensions within.”3 This internal tension gives rise to creation through encounters with “the other,” something that destabilizes the idioculture of an individual–“it is this instability and inconsistency, these internal and external pressures and blind spots, this self-dividedness, that constitute the conditions for the emergence of the other.”4 Attridge’s concept of creation as arising from a divided self is manifested literally in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, in the relationship between Frankenstein and his creation.

The other, when defined as the unknown, may seem at first to be incompatible with science. How can otherness still exist in modernity, when we have so much knowledge about the world? But science often raises questions long before it answers them, and the tension between the mystery of creation with the burgeoning field of medical science powers the novel.

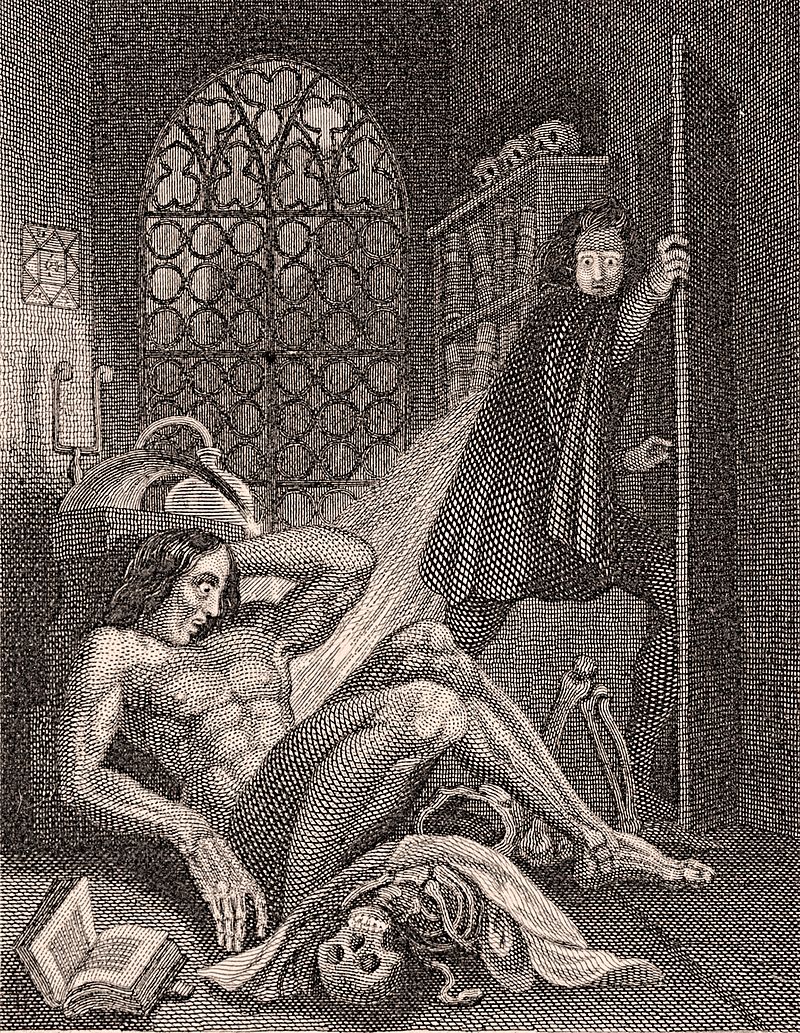

by Joseph Wright (1771)

Victor Frankenstein, in other words, has an idioculture that is fundamentally at odds with itself. As a young boy, Frankenstein enjoys studying the alchemists. While the alchemists were long discredited, Frankenstein prefers the alchemists’ lofty goals such as immortality to the more mundane goals of contemporary science. Frankenstein has “a contempt for uses of modern natural philosophy. It was different when the masters of the science sought immortality and wealth;–such views although futile were grand; but now it was all changed.”5 So he seeks to push science to its limits, combining the ambition he gained from reading the alchemists with his knowledge of contemporary chemistry to create “a human being…of a gigantic stature”–his creation.6

The moment when the creation is given life bears a striking resemblance to Georg Hegel’s passage “Self-sufficiency and non-self-sufficiency of self-consciousness; mastery and servitude” in Phenomenology of Spirit, commonly known as the “master-slave dialectic,” where identity is formed through encountering the other in the form of another human being. Before the creation took its first breath, Frankenstein is unbothered by its monstrous appearance, viewing his creature in much the same way as his “trifling discoveries in the improvement of some chemical machines.”7 It is only when the creation became alive, and recognizable as another entity not unlike himself, that Frankenstein reacts to it in horror. The creation, until that point, “exists as an unessential object,” but now “the other is also a self-consciousness, and thus what comes on the scene here is an individual confronting an individual.”8 It is this moment of recognition, this awareness of being observed, that will affect Frankenstein’s actions for the rest of the book.

The creation does not only suffer from the violence that is enacted on him, but also by the lack of recognition he is shown. He is viewed as an other, that is, not fundamentally different but at odds with the culture in which he was created it–“[to] be other is necessarily to be ‘other than’ or ‘other to’.”9 The otherness of the creation represents something that is present but unacknowledged in Frankenstein–the philosophical issue of what it means to be a created being.

Shelley did not only title her novel The Modern Prometheus because of the creative power Frankenstein harnessed that had previously only been the realm of deities, but because of Prometheus’s prior actions–creating man from clay, an obvious parallel to the Abrahamic creation story. Frankenstein is not only a story about the power of science, but a story asking about the responsibility of a created being to its creator, and the responsibility of a creator to his creations. Frankenstein is a philosophical, theological novel.

(Constantin Hansen, c. 1845)

Self-consciousness “exists for another self-consciousness; that is to say, it is only by being acknowledged or ‘recognized’”–so the experiences of Frankenstein and the creation are fundamentally intertwined.10 Frankenstein dreams of creating a creature that “would bless [him] as its creator and source; many happy and excellent creatures would owe their existence to [him] in a manner no father could claim the gratitude of his child.”11 He is viewing the creation as an object to build his own identity upon, not as a self-consciousness like himself. The story of Frankenstein could have been about creating something new from the meeting of two very different beings, but in the moment Frankenstein fled from his creation in disgust, it became a story of destruction, a relationship where “there is no creativity, no response to alterity and singularity…also an invention of the other, but in order to exclude it.”12 Creation is only possible when the other is embraced.

NOTES

1 Alpheus Spring Packard. Lamarck, the founder of Evolution: his life and work with translations of his writing on organic evolution. (New York: Longmans, Green, and co., 1901).

2 Derek Attridge. The Singularity of Literature. (Routledge, 2004), 21.

3 Attridge, 25.

4 Ibid.

5 Mary Shelley, with Percy Shelley. The Original Frankenstein. Edited by Charles E. Robinson. (Vintage Classics, 2009), 267.

6 Shelley, 273.

7 Shelley, 270.

8 Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel. Phenomenology of Spirit. Translated by Terry Pinkard. (Cambridge Hegel Translations, 2013), 164.

9 Attridge, 29.

10 Hegel, 161.

11 Shelley, 273.

12 Attridge, 151-2.

Excellent research and analysis of one of my favorite novels! I teach this novel to my 11th grade lit students and I will share your essay with them.

LikeLike

Thank you so much for your kind words. It’s one of my favorite novels as well!

LikeLike