(Johann Ulrich Krauss, c. 1690)

T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land aspires for universality and the disruption of boundaries between one character and another. But the stated goal of creating a poem where “all the women are one woman” presents challenges, potentially leading to a work that lacks nuance.1 The women in The Waste Land, while they have an important role to play, are nonetheless constrained by the tropes and archetypes that Eliot draws on to construct his narrative. However, the poem also uses these archetypes in ironic ways, updating them to a more modern era, including women in roles previously not occupied, and presenting women as more multifaceted than in the original myths alluded to.

The Waste Land can be read as an allegory for the Fisher King legend. While there have been many variations of the story, most commonly King Arthur is wounded and unable to do anything but fish while his land becomes infertile around him. Only the Grail is able to return the king–and the land–back to health. This legend contains themes and motifs common throughout world mythology, as was explored in Sir James Frazer’s The Golden Bough and Jessie Weston’s From Ritual to Romance, the later text being a major source of inspiration for Eliot. From Ritual to Romance explores the idea of a universal “vegetation ceremony,” or a shared myth among disparate cultures relating the health of the land to the sacrifice of a king.

Traditions from ancient Egyptian polytheism to Christianity all have stories about a connection between the death of a king and the fertility of the land. In many stories, there is a direct connection between the youth and masculinity of the king with the fertility of the land. Weston related a belief from the Shilluk people of modern-day South Sudan, where if the king is “allowed to become old or feeble…[where one] of the signs of failing energy is the King’s inability to fulfill the desires of his wives,” he must be killed or the land will come to ruin and his people to misfortune.2

Additionally, King Arthur is described as being wounded in the upper thigh or groin, depending on the telling, which many have interpreted as him being castrated or otherwise rendered impotent. This view of reproductive ability as a source of agency and power becomes more complicated when looking at the role of women in the poem.

Unlike many other characters in The Waste Land, both Tiresias and a fisherman (presumably the Fisher King) talk in the first person. While Tiresias is closely associated with all of the characters in the poem, as he observes and inhabits the minds of all the characters, he nevertheless does bear a striking resemblance to the Fisher King. He is passive (“a mere spectator and not indeed a ‘character,’”), sits by the side of the water (“I who have sat by Thebes”), and lacks traditional signs of virility (“Old man with wrinkled female breasts”), just as the Fisher King does.3 If Tiresias is read as a Fisher King figure in his own right, it means that the failure of the land is, if perhaps not his fault, then certainly closely linked to him. A visionary figure, Tiresias is nevertheless powerless to change the situation he helped create.

As Tiresias is, in some ways, every character in the poem, his position as the Fisher King helps to capture the paralysis and frustration felt by many in the Lost Generation, where “the only relief of a personal and wholly insignificant grouse against life” was to hope for the destruction that would inevitably bring about rejuvenation.4 Throughout the poem, women are placed in situations that, while could be viewed as misogynistic, could also be read as a depiction of the claustrophobia felt by a society that limited their choices. While Tiresias might be able to be “throbbing between two lives,” women throughout the majority of history weren’t able to.5

Robert Graves and Carl Jung popularized the idea of a universal “triple goddess” myth. For example, the Roman deity Diana was considered in the ancient Roman to be three goddess known as Diana triformis— goddess of the hunt, goddess of the moon, and goddess of the underworld.6 It is important to note that interpretations of the triple goddess archetype as containing a “maiden, mother, and crone,” while initially common in academic works, are considered today to be of dubious historical value. Regardless, interpreting womanhood as falling into three distinct stages (a lover or object of desire, a mother, and an elderly or wise woman) is prevalent throughout art and literature, even if the conflation with the triple goddess archetype may be more contemporary to Eliot than the Greeks.

Three women who have the most character development in the poem are the typist, Lil, and Madame Sosostris, who fit neatly into the maiden, mother, and crone archetype. The typist and Lil are two characters who, in a reversal of the Fisher King myth, suffer due to sexuality and reproductive ability. The typist, although perhaps archetypally an object of male desire, is described with surprising depth and even respect by Tirseas. As he had experienced life as both a man and a woman, he has “foresuffered all / Enacted on this same divan or bed,” and is able to tell the events that follow without the Romanization of the previously references painting of a “sylvan scene” of Philomela being changed into a nightingale after being assaulted by her brother-in-law.7

At the same time, however, Philomela was able to take revenge on her brother-in-law (in most versions, he has his head chopped off), while the typist is unable to do anything but think “Well now that’s done: and I’m glad it’s over.”8 This sense of paralysis creates a thematic link between the typist and the Fisher King, who was also robbed of his agency, although in a much different way.

Lil, an ironic allusion to the archetypal mother, likewise feels constrained by the expectations placed on her. A friend of hers, another woman, derides her appearance and tells her that she should get a set of false teeth before her husband, Albert, comes back from the army, or otherwise, the friend claims, he will cheat on her. However, it is revealed that the reason for her appearance was that she took pills in order to induce an abortion, as, since she almost died from giving birth to her fifth child, she didn’t want a sixth. But her friend dismisses this, saying “What you get married for if you don’t want children?”9

Here, the focus is on societal pressure to have children at any cost, and Lil must decide between risking her life to have more children or living with the knowledge that her husband will most likely begin to cheat on her. Any other reason for Lil to have children is not mentioned, and, when looking at the image of a woman surrounded by bats with baby faces in the last section of the poem, “What the Thunder Said”, the implication seems to be that there is no reason for anyone in the Lost Generation to have children at all, knowing that after World War I they will be growing up in a new, dangerous, and fragmentary world.

Madame Sosostris, alone among these three female characters, seems to have some sort of answer to the existential ennui faced faced by so many of the figures in the poem. While she may at first seem to be a comical character, with “a bad cold” and a deck of tarot cards, her method of deriving meaning out of the chaos of the present is not unlike Eliot’s writing style in The Waste Land.10 They both mix literary allusions, obsolete supernatural beliefs, and popular culture into something that resembles something new and modernist.

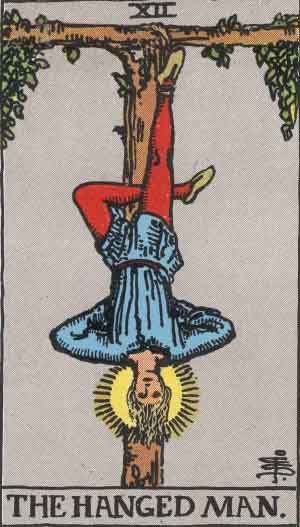

Madame Sosostris’s advice to “[f]ear death by water” is closely mirrored by Eliot’s motif of water as a destructive force.11 Eliot explains most of the symbolism of her tarot cards in the notes (the Phoenician sailor and the merchant are characters later in the poem, crowds of people and death by water also appear, and Eliot “quite arbitrarily” associates the Man with Three Staves with the Fisher King) but the Hanged Man requires more context to understand, as Eliot uses it to allude to both Frazer’s Hanged God and the third man.12

Frazer, author of The Golden Bough, proposed the Hanged God as a universal mythic archetype, similar to the triple goddess or the vegetation ceremony. Both the Norse god Odin and the Christian figure of Jesus were executed on a tree (through hanging and crucifiction, respectively) but later were resurrected and gained knowledge about the universe. The third man refers to the latter version of the Hanged God trope, specifically, the story of what came after Jesus came back from the dead, when he was walking with two disciples who didn’t recognize him.

However, the language Eliot uses to describe this gives it a modern twist. While Eliot directly refers to his description of the third man as being inspired by Ernest Shackleton’s account of his journey to the South Pole, specifically a section where his team of explorers are suffering from “the constant delusion that there was one more member than could actually be counted,” Eliot does not provide an explanation for writing how it was unknown “whether [the third, hooded figure was] a man or a woman.”13

This inclusion of women into an archetype that has historically only been filled by men is very interesting, and perhaps the clearest moment of Tiresias as a universal symbol. In The Waste Land, the third man is not meant to be a godlike figure, but a representation of the entirety of the Lost Generation, who all have undergone metaphorical death and resurrection, and none more than Madame Sosostris, who broke out of paralysis and created meaning from the rubble of the past.

Notes

1 T. S. Eliot. The Waste Land. (London: Hogarth Press, 1923), n218.

2 Jessie Weston. From Ritual to Romance. (Cambridge University Press, 1920), 55-6.

3 Eliot, n218, 245, 219.

4 Eliot, comment to Henry Ware Eliot Jr.

5 Eliot, 218.

6 C. M. C. Green. Roman Religion and the Cult of Diana at Aricia. (Cambridge University Press, 2007).

7 Eliot, 243-4, 98.

8 Eliot, 252.

9 Eliot, 164.

10 Eliot, 44.

11 Eliot, 55.

12 Eliot, n46.

13 Eliot, n359, 364.